I was at work when I got the call.

At the time, I didn’t actually realise it was the call. I just thought it was a call. Of course, modern men are notoriously simple creatures, and none more so than the typical expectant father. It can take them anything up to nine months to come to terms with their dad-to-be status, and just as they’re finally getting used to it – along comes the call. It’s little wonder that so many of them adopt a classic ostrich posture when it comes to imagining how they’ll cope – and what they’ll actually have to do – once their partner makes that hopefully inevitable transition from being pregnant to being in labour.

But I won’t be too hard on myself. Clare thought it was just a call, too.

She’d had what is commonly referred to as ‘a difficult pregnancy’. If you don’t know what one of those is, just ask around, look it up or use your imagination. Once you’ve done that, multiply your initial findings by a generous factor then look upon that as a conservative estimate. If you don’t know what a conservative estimate is, then I suggest you try a difficult pregnancy.

One of the ways in which I tried to compensate for what Clare was going through was to schedule my lunch break at work to coincide with home time at school. By doing this, if things got tough on the ranch I could always lighten Clare’s load by collecting my smart and impressionable five year-old stepdaughter – Lily – from Broadmeadow Infants. Clare may have endured long months of hormonal upheaval, psychological turmoil and physical pain, but at least I was doing my bit.

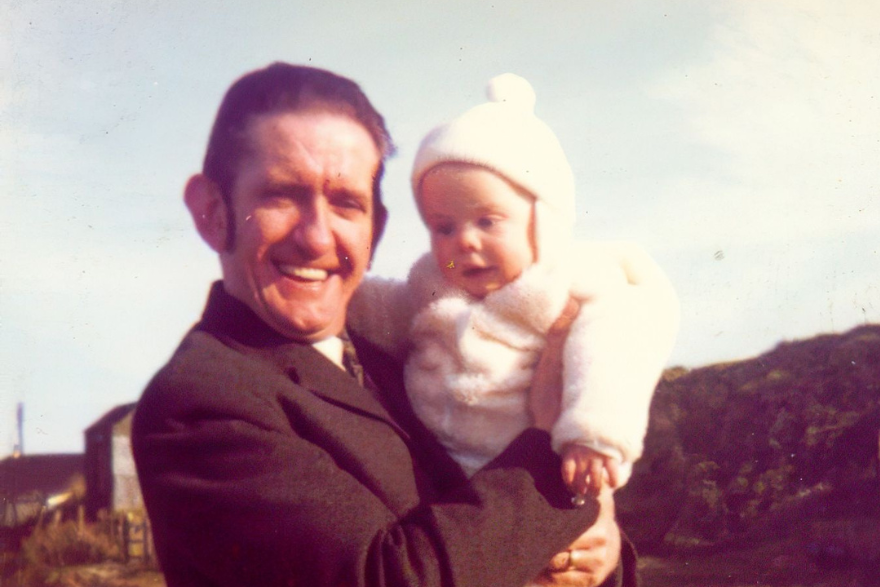

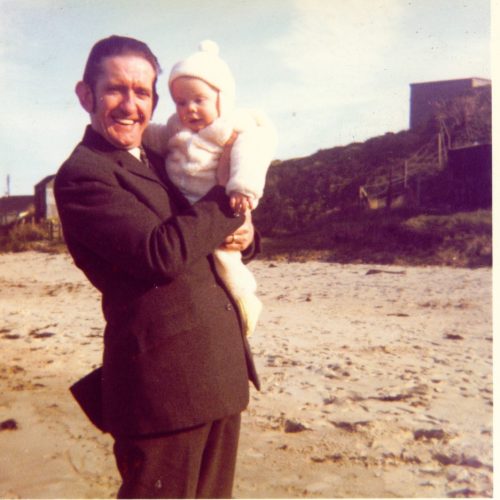

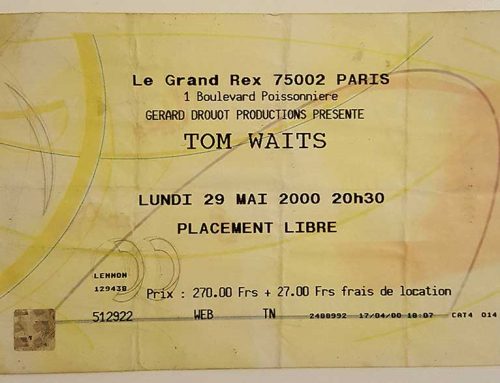

I don’t know what my paternal grandfather – Patrick Lennon – was doing when he got the call, but I imagine he was probably working on a field and not getting so hung up on navel-gazing and petty semantics. He was a hard working Irish farmer of modest means at a time when babies were usually born at home, so “the call” was probably just a panicked shout from the cottage. In those days, phones, cars and commuting were luxuries hardly anyone could afford.

It was 1930, a personal annus mirabilis that marked the arrival of many of my favourite heroes. Clint Eastwood, Sean Connery and Gene Hackman all made their inconspicuous off-screen debuts, while Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins all touched down on our world for the first time. More significantly – for me, at least – it was the year my dad was born.

Paddy Joe Lennon was born near Bellaghy, County Derry (or Bellaghy, County Londonderry, depending on your own semantic hang-ups). The cottage in which he was born has long since been demolished, but I can still remember visiting it when I was younger than Lily is now. It was an abandoned old building with bare, broken floorboards, and my lasting memory was a profound, tangible fear of falling through the gaps and cracks underneath me.

My dad’s mother once told my mother that when he was born he was a very delicate baby. This always sounded to me like one of those typically Irish euphemistic understatements, and when I was reminded of it recently I struggled to reconcile this image of infant fragility with the strong man I knew, the person who would go on to be my biggest inspiration.

I never met my grandfather, another Patrick Lennon. He died when my dad was fourteen months old. As I think about that, once again I feel like the child walking over those bare, broken floorboards.

When I got the call that I thought was just a call, Clare was in a bad way at the ranch and asked if I could pick Lily up from school. I explained to my boss what was happening and was about to leave the building when I was intercepted by two female colleagues, Chris and Lynne, both of whom are mothers. “We’ve had a whip-round,” said Lynne, handing me a Mothercare bag full of gift-wrapped items.

“Thanks,” I said, “that’s very kind. I’ll pick it up when I get back.”

“Best to take it now,” said Chris, knowingly.

I drove to Lily’s school, promptly picked her up and swiftly sped her home. As soon as I walked through the front door, though, I realised that this wasn’t going to be like those other times. Instead of the usual greeting, Clare told me she was having contractions.

My thoughtful, considered reply consisted of two words.

By today’s standards, my dad’s childhood is difficult to imagine. As the only boy in the family (he had four wonderful older sisters), from an early age much of the arduous physical labour on the farm would have fallen on his little shoulders. He’d be up at cock crow, work hard, run to school, run home, work hard then go to bed. It’s worth remembering things like that next time you hear someone claim that their lack of broadband access is a human rights violation.

As he got older he forged what would become lifelong friendships with a group of local boys who – later in life – would go on to become his brother-in-laws and eventually my uncles. He learned to play the accordion and joined a local Hibernian band. He fell in love, got engaged and ended up getting his heart smashed to smithereens.

In the late 1950s he left the farm, Bellaghy and Ireland and moved to Birmingham, England in search of work.

Decades later, Clare, Lily and I are bundling ourselves into my Citroen Saxo and making our way to the hospital in Edgbaston via my mam’s in Kingstanding. Lily was going to stay there as Clare and I had both agreed that a Maternity Ward filled with women screaming obscenities that would make Malcolm Tucker blush was no place for a smart and impressionable five year-old, especially when the loudest and most offensive screams would probably be emanating from her mum.

A maternity ward is no place for a child.

Despite a similar sounding syllable, Kings Norton and Kingstanding are situated at opposite ends of Birmingham. Having said that, ‘opposite ends of Birmingham’ can hardly be described as an epic quest or the stuff that Michael Palin travelogues are made of. Under normal circumstances, at least. On that day – and under those particular circumstances – the journey felt like a demented mash-up of Tolkein, Kerouac and Hunter S. Thompson. I’d like to say I was sophisticated enough to have made those literary comparisons at the time, but unfortunately the only fictional precedent I could think about was a pregnancy sub-plot in an On The Buses film.

Clare was panting in the passenger seat while I was panicking in the driver’s seat. She had a watch in one hand and was making notes with the other, timing her contractions. A quick glance at her notepad confirmed my worst suspicions.

They were getting closer.

On St Valentine’s Day in 1961 it was snowing heavily in Birmingham. Paddy Joe Lennon – the eternal Irish country boy in the big city – was working at Fisher and Ludlow’s in Castle Bromwich. That evening, he went to a dance at St Chad’s Hall in the city centre and met a young Irish nurse called Rose. As they left the hall, they slipped on the ice and she broke her three front teeth.

On St Patrick’s Day in 1965 they got married.

It’s 2009 and we’re dropping Lily off at my mum’s and heading to the Women’s Hospital in Edgbaston.

Maybe it was a coping strategy, but along the way stupid, banal thoughts kept racing through my head. Most of them had to do with the practical considerations involved in parking at a maternity hospital. I don’t know why I was getting so anxious about this, but reason and relevance were never key players in my coping strategies. I’ve never needed anything as dramatic and as life-changing as my partner on the brink of labour to make stupid thoughts go racing through my head. Just breathing normally does it.

As we reached the hospital, I found myself mumbling Jewish country singer-turned-detective novelist Kinky Friedman’s famous prayer for drivers:

Hail Mary full of Grace

Help me find a parking space

Which, miraculously, seemed to work. I nabbed a vacant spot right next to the door and the pair of us legged-it with gusto through the corridors until we eventually found the check-in desk. A porter and a nurse were engaged in what looked like some heavy flirting and Clare and I felt slightly awkward. We didn’t want to interrupt. I found myself thinking of Carry On Matron – the one in which Sid James and his gang plan a contraceptive pill heist in a maternity hospital – and made a mental note to review my habit of dealing with stressful situations by thinking about smutty British films.

Eventually, a contraction made its presence felt. So we did the same.

In 1966, my parents moved to Carrickfergus, County Antrim. It was a pretty coastal with a Norman castle on the shore and seemed like the ideal place to raise a family. Within a few years, a grim, typically Irish euphemistic understatement enters the language.

The Troubles begin.

Clare and I are escorted to a waiting room where we wait. And wait.

People came and went. Different ages, races, shapes and sizes, all there for the same reason. Thinking back now, it seems like one of those time-lapse films in a natural history programme. In the distance we could hear a frenzied scream. We looked at each other, squeezed each other’s hands, said nothing.

Then it was our turn.

In 1970 I arrive on the scene, and in 1973 my first and only brother turns up. According to family legend, when I was brought to the hospital to meet him for the first time, I produced a concealed stick and attempted to hit him over the head with it. This characterised our relationship for many years. He still likes to remind me of it now.

We’re in the ward and Clare is in agony. A nurse offers her paracetemol.

“I don’t want paracetemol,” Clare snarled. “I want the good stuff.” The nurse offered her Pethadine. “That’ll do.”

I felt slightly afraid.

By the early 1970s, the pretty Northern Irish coastal town of Carrickfergus has become a hotbed of vicious sectarianism. Due to an accident of theology, my parents had to endure what modern commentators would refer to as “institutionalised discrimination” and “systematic persecution”. At least they didn’t have to worry about a lack of broadband access.

In 1976, Paddy Joe Lennon was having a drink with a friend and colleague who’d had too many. As my dad got up to leave, the man said: “If civil war breaks out I’ll come ‘round to your house and shoot you, your wife and your children.”

My dad loved his family, so responded in an appropriate manner. Shortly afterwards, we left Carrickfergus and moved to Birmingham.

It’s 2009, and Clare is in a wheelchair being rushed to the delivery suite. At one point the porter misjudged a turn and Clare and her wheelchair almost crashed into a wall. Clare cracked a weak joke about Ayrton Senna. It must have been between contractions.

For as long as I can remember, my dad was my hero, my best friend and role model. He was the perfect combination of innocence and wisdom, the eternal country boy in the big city. He’ll always be the smartest person I’ve even known, the funniest person I’ve ever known, the most charismatic person I’ve ever known and the most compassionate person I’ve ever known. When I was old enough to drink, he was my favourite person to go to the pub with. He was the person I turned to when my heart first got smashed to smithereens, and he knew what to say and what not to say because he knew exactly what I was going through. My family adored him. My friends adored him. I adored him.

In 1995, while making me a cup of tea, he died suddenly. He was buried on St Patrick’s Day that year. It would have been my parents’ 30th Wedding Anniversary.

I didn’t know what to expect from the delivery suite. Maybe I hadn’t done my research, but I sort of expected a crack team of paper-masked professionals. What I didn’t expect was a midwife who bore an uncanny resemblance to Clare’s mother. That slightly freaked me out, as they say in certain circles.

At about 1am Clare’s waters broke. For the next hour, she experienced levels of sustained pain that I can’t begin to imagine. I kept holding her hand and making reassuring noises. She kept screaming “I want a Caesarean” and “If you love me, you’d get me an epidural”. Unimaginable levels of pain will make you say things like that, I guess.

My dad came into this world on 24th April 1930. We don’t know what time he was born because in those days people didn’t keep track of things like that. Exactly seventy-nine years later – on 24th April 2009 at just after 2am – his first granddaughter was born. She was strong, beautiful and perfect.

I cried like a baby. He would have understood.

This article first appeared in Dirty Bristow magazine.