These days, a visit to the cinema wouldn’t be complete without someone tripping over a cape. From superheroes like Batman and The Avengers to less obvious examples like Oldboy and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, films based on comic books seem to be cluttering up the multiplexes at a seemingly exponential rate. As A-list actors and directors continue to embrace a medium traditionally despised by mainstream pundits, this particular fad has given rise to another, lesser-known phenomenon: high profile creators from the glamorous world of film and TV are now queuing up to make comic books. Keanu Reeves and Emilia Clarke are the most recent additions to an illustrious list that includes Hollywood filmmakers Kevin Smith and Joss Whedon, all willing to take big pay cuts to fulfil their childhood dreams. In Europe, however, this particular media migration path is nothing new. For decades now, one of the hottest names on the sophisticated Eurocomics scene has been a 90-something Chilean who also happens to be one of the most notorious film-makers in the history of cinema.

Alejandro Jodorowsky has carved out a unique career for himself as the creator of cult, controversial movies and crazed, uncompromising, visually stunning comics. For fans of his work, this decade’s been something of a golden age: not only has he been directing movies again – including 2015’s semi-autobiographical The Dance of Reality (his first in 24 years), and it’s follow-up, Endless Poetry – but there’s also been Jodorowsky’s Dune, an award-winning documentary looking back at his madly-ambitious and famously unmade 1970s film adaptation of the classic sci-fi novel. There’s even been a steady stream of new Jodorowsky authored comics (well, new to English language readers, at least), including two new series based on his acclaimed Metabarons stories and a graphic novel sequel to his breakout movie, El Topo.

However, while his Hollywood comic writing counterparts are seemingly content with rejuvenating the superhero genre – breathing new life into a bunch of decrepit Dayglo demigods – Jodorowsky’s approach to the medium has been somewhat more ambitious: he’s created an entire fictional universe of interconnected stories, concepts and characters that are uniquely his own. Fans call it ‘The Jodoverse’ and, in the words of Warren Ellis, it’s ‘astonishingly beautiful and totally mad.’

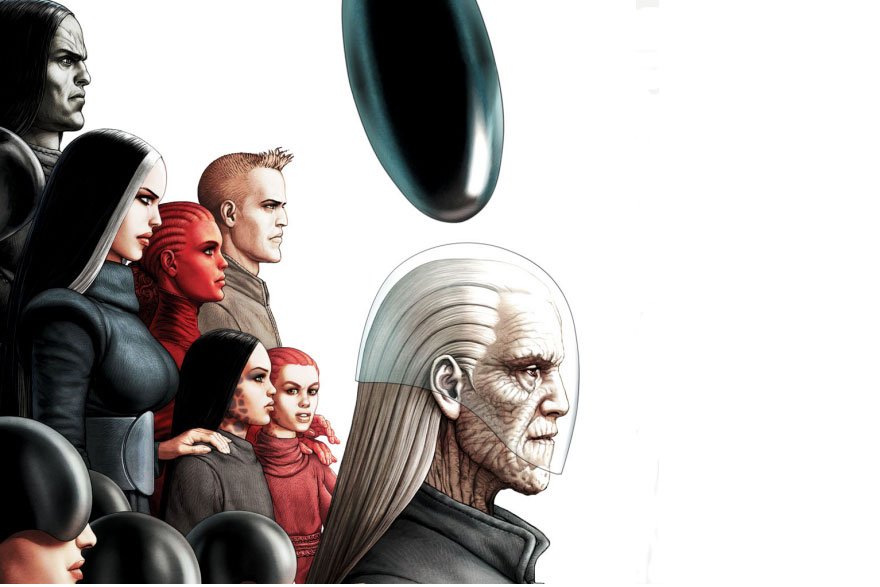

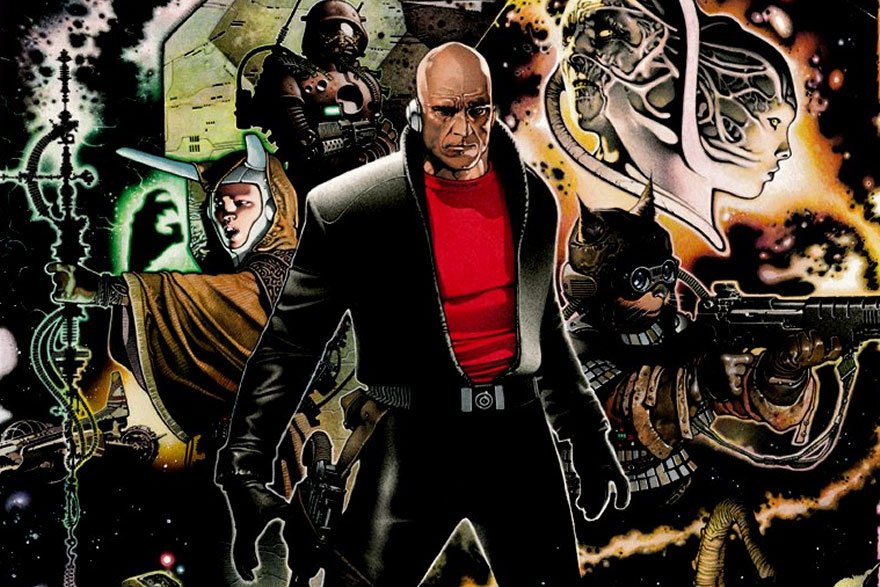

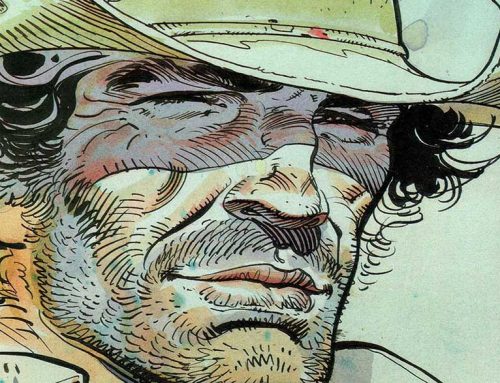

For the uninitiated, The Jodoverse is made up of a sequence of serialised ‘bande dessinée’ (for that’s what the French call ‘em) comic albums including The Incal, The Technopriests, Megalex and – in the humble opinion of your author – Jodorowsky’s comics masterpiece, The Metabarons. The latter is a multigenerational science-fiction epic that chronicles the rise of the eponymous protagonists from humble stonecutters on a marble planet to the galaxy’s most formidable warriors. Brutally violent, emotionally-charged and almost operatic in tone – with deeply flawed yet honourable (for the most part), multi-layered characters – The Metabarons is quite unlike anything you’re ever likely to see in any medium. Published by French comics house Les Humanoïdes Associés – and featuring sumptuous art by the late Argentinean artist Juan Giménez – it combines solid storytelling rich in subtext with jaw-dropping visuals. Since its English language debut over two decades ago, the series has become both a critical and commercial success, attracting rave reviews, endorsements by top comics pros and a word-of-mouth buzz that continues to entice new readers.

Oh, and it also happens to be completely insane.

With The Metabarons you never know what demented notion, wild concept or surreal image Jodorowsky and Giménez will smack you over the eyes with next. It might be a huge fleet of alien vessels hidden within a fake planet, or perhaps a coven of scheming witches who travel through space on a giant fish. It might even be a floating boy who mutilates his feet just to earn the respect of his father. To quote Ellis again, ‘There is literally a new and mad idea on every page.’

Jodorowsky, it must be said, is no stranger to such buggier-than-batshit craziness. He made his name directing cult, avant garde films like El Topo, The Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre – three perennially shortlisted candidates for the Weirdest Goddamn Movies Ever Made award. This is a man who once claimed that ‘most directors make films with their eyes, I make films with my testicles.’ Is it any wonder, then, that his comics are nuts?

His fiery, feverish and seemingly boundless imagination permeates The Metabarons and the rest of his Jodoverse titles and, unlike the work of other media migrants, his comics – with their combination of visceral imagery and esoteric depth – are thematically inseparable from his movies. Both are the culmination of a lifetime of artistic experimentation, reflecting his passionate obsession with self-transformation, mysticism and violence. In this sense, The Jodoverse is a continuation of the same artistic alchemy by different means.

Gallery: The Metabarons by Jodorowsky and Giménez

(Click images to enlarge)

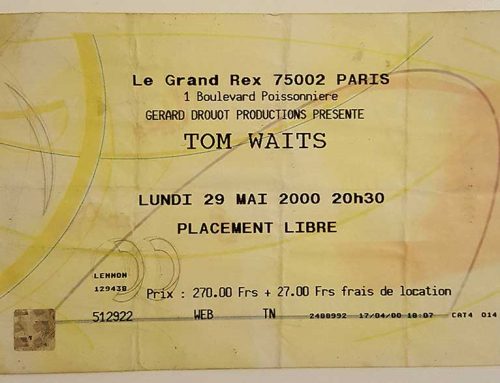

During the 1960s Jodorowsky moved to Mexico, directed stage plays and created a weekly comic strip called Fabulas Panicas for one of the country’s leading newspapers. His comics career had to be put on hold, however, once he became involved with the fledgling ‘Mexperimental’ cinema scene. His first feature length film, 1968s Fando Y Lis, almost resulted in him getting lynched by an outraged crowd for its perceived attack on traditional values. He followed it up with El Topo (1970) , a mystical, allegorical, dreamlike Western (or, more accurately I suppose, Eastern) which made his name internationally. A stylish head-on collision between the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone and the Surrealist cinema of Luis Bunuel – a ‘Fistful of Dalis’, if you will – El Topo is a brutal film brimming with violent imagery, Taoist philosophy and some of the most hilariously blatant phallic symbolism you’re ever likely to see. Upon its release in the US the following year it quickly gained a cult following on the midnight movie circuit, with John Lennon hailing it a masterpiece and convincing his notorious manager, Allen Klein, to buy up the distribution rights and produce Jodorowsky’s next film, The Holy Mountain (1974).

These films contain many of the thematic obsessions that would later permeate The Metabarons and the rest of the Jodoverse. The spiritual quest – a theme that dominates all three films – would be further explored in his seminal comic series The Incal. In El Topo, for instance, the hero has to prove himself by killing four master gunslingers, while in The Incal protagonist John DiFool has to confront his four conflicting spiritual elements: on both occasions, these hostile quartets represent obstacles to the evolution of man. Transcendence through pain is another example. His 1989 film Santa Sangre, in which the youthful protagonist’s cruel father forces his son to have a tattoo of a phoenix carved on his chest, has a direct parallel in The Metabarons, in which each new generation undergoes a ‘mutilation initiation’ and inherits the family crest, a glowing bird-shaped birthmark.

At the root of these themes and symbols is transformation. As Jodorowsky himself once said: ‘All my comics, all my movies, they are the starting of a change in all levels.’ While this helps illustrate the unity in Jodorowsky’s oeuvre, however, it doesn’t explain how his comics Jodoverse came into being in the first place. For that, we must turn to one of the most influential science-fiction films never made.

Jodorowsky’s Dune is one of those legendary unmade films – like Orson Welles’ Don Quixote or even Terry Gilliam’s Watchmen – that cinephiles will speculate about in hushed, reverential tones for generations to come. Based on the classic science fiction novel by Frank Herbert, pre-production began in 1974 on a project of jaw-dropping scope, scale and ambition. Pink Floyd, at the peak of their creativity, agreed to score the soundtrack while a bizarre cast was assembled that included Mick Jagger, Salvador Dali, Gloria Swanson and the aforementioned Welles. Jodorowsky also gathered about him an unprecedented cadre of artists to help bring the story to life: a young Dan O’Bannon was hired as special effects supervisor, while Swiss artist H.R. Giger and French comics legend Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud designed characters, environments and storyboards for the film.

According to Jodorowsky, he and Moebius formed an instant bond while working on the movie: ‘We worked eight hours a day on that film, for months and months. We were both in total resonance with each other. Moebius drew so fast that it was just incredible. His pen almost miraculously created all the travellings, the panning shots, the zooms I wanted. Through [the] three thousand plus drawings he did for Dune, I could feel just as if I had actually shot the picture. Anyone looking at his work would feel that they had experienced the film as fully as if they had seen it on a screen in a theatre.’

Which, of course, was just as well for after two years of hard work the project ground to a halt. Herbert was unhappy with Jodorowsky, accusing the director of taking liberties with his novel (which he did), and the financial backing dried up. The significance of Jodorowsky’s Dune, however, was in its failure: it became a major creative catalyst. O’Bannon, Moebius and Giger subsequently hooked up with Ridley Scott to create the classic movie Alien, and Jodorowsky and Moebius started making comics.

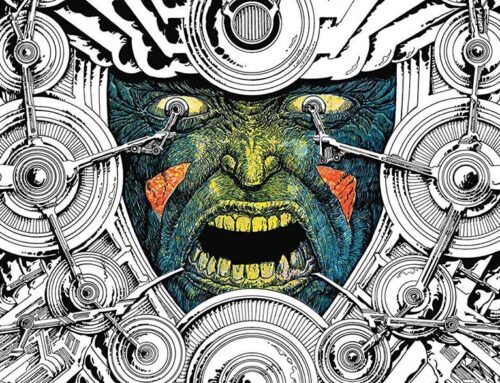

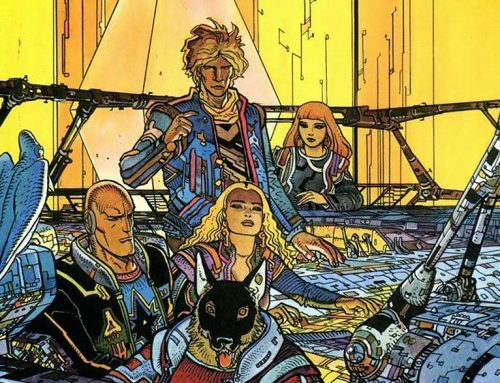

Set in a nightmare subterranean dystopia some 10,000 years in the future, The Incal introduces us to DiFool, a grubby Private Eye who finds himself the reluctant protagonist in a cosmic conspiracy of breathtaking proportions. At the heart of the story is the quintessential Jodotheme of transformation: DiFool, according to Jodorowsky, ‘never stops changing. He metamorphoses, progresses, sometimes regresses.’ The series, in fact, gathered together all the elements that characterised his movies and fascinated him throughout his life – the spiritual quest, violent transcendence, esoteric symbolism – then cranked them up to a cosmic scale in a beautiful synthesis of word and image.

The Incal continues to inspire many of today’s top creators – Kick-Ass co-creator Mark Millar calls it ‘one of most perfect comics ever conceived’ – and it was successful enough to spawn prequels, sequels and numerous spin-offs including, of course, The Metabarons.

Gallery: The Incal by Jodorowsky and Moebius

(Click images to enlarge)

Jodorowsky fans, though, aren’t likely to get too excited by this news: they’ve heard this sort of talk before and they’ll believe it when they buy their ticket and see it. The director’s twenty-four year celluloid sabbatical was littered with tantalising movie projects – most notably a sequel to El Topo and a David Lynch-produced ‘metaphysical spaghetti western of gangsters’ called King Shot – that all ended up banished to the same corner of development hell as his Dune film (although at least the former has been turned into a graphic novel series featuring stunning art by Mexican artist and frequent Jodorowsky comics collaborator, José Ladrönn).

The Incal movie will probably end up there, too. Unlike many other comic book mythologies, the Jodoverse doesn’t lend itself well to the four-quadrant, please-everyone dynamic of the modern big screen blockbuster. It’s a deeply personal, ferociously uncompromising creation that channels a lifetime of artistic and spiritual exploration into a lurid brew of madness, genius, breathtaking beauty and often appalling brutality. It has something to offend everyone, yet bringing it to life would require the sort of budgetary excess that would make James Cameron look like Jim Jarmusch. For the foreseeable future, then , The Jodoverse will probably remain unfilmable.

And so it should be: that’s what makes it the perfect comics universe.

This is a significantly updated and revised version of an article that originally appeared in comics magazine Borderline.