It’s St Patrick’s Day 2019, and I’m revisiting a thing I originally wrote in 2008. On 11th November of that year I took part in a gonzo social experiment that involved circumnavigating the city of Birmingham on the number 11 bus and recording my observations. It had something to do with a thing called ‘psychogeography’, which is a weird term because at my old school it was always the history teachers you had to look out for.

Incidentally, St Theresa’s Social Club is no longer with us, bulldozed some years ago to make way for apartments. I never did make that return visit.

At about 2.25pm on the 11th November 2008 the number 11 bus – my number 11 bus – makes its way along Church Lane, past Hamstead Road, up Wellington Road and down Memory Lane.

We’re in Perry Barr, now, and – seeing as how I spent many of my formative years living in nearby Kingstanding – this stretch of the route turns out to be pretty damn evocative for me. Many of the buildings we pass seem to resonate with all kinds of personal significance and I soon find myself embarking on an unscheduled detour via the outer circle of my brain. There was no mention of that in the timetable.

Over there, to the left, is the Holy Roman Catholic parish church of St Theresa’s. That gets me thinking about two of my closest friends – both former parishioners – and of gatherings, both happy and sad. Next, to the right, is a garden centre. A dim, nebulous childhood memory flickers and sizzles and struggles to take form. It seems to involve me shopping for shrubbery with my parents on a wet Sunday afternoon in 1981. I decide to let it go.

Then, just a little further along and to the left, I catch a glimpse of a modest-looking building you probably wouldn’t notice if you didn’t already know it was there. Tucked away just off Wellington Road, behind what used to be a bed warehouse, is St Theresa’s Social Club.

St Theresa’s Club in Perry Barr used to be one of my family’s most regular haunts. It’s been more than a decade since I last paid it a visit and, as we pass it now, I find myself sliding into a synaesthetic spiral of sentimentality. Family snapshots cascade through my cortex as I taste the velvety richness of a perfectly-pulled pint of Guinness, smell the aroma of stale cigarette smoke and hear the sound of Irish Music being played with varying degrees of authenticity. The experience is quite overpowering and leaves me feeling a bit like a bad Caffreys ad.

St Theresa’s was a focal point of the North Birmingham Irish community for decades. My cousins worked behind the bar there as teenagers in the early 80s, and it’s where one of them met her future husband. Later, when it was my turn to be a teenager, I’d often go there for a drink and the regulars I got to know were usually friends of my parents’ who, like Mum & Dad, were part of that big wave of Irish migrants who arrived in Birmingham during the 1950s and 60s. I shared many a raucous night in their company and – despite the not inconsiderable age gap – they were often more amusing, unpredictable and interesting than many of my peers. Back then, they’d often comment on how much better the place was in the old days, but from my experience their demographic they usually said that about most places. Of course, if I got off the number 11 bus and popped into St Theresa’s now I’d probably also comment on how much better it was in the old days. From my experience of my demographic, we say this about most places, too.

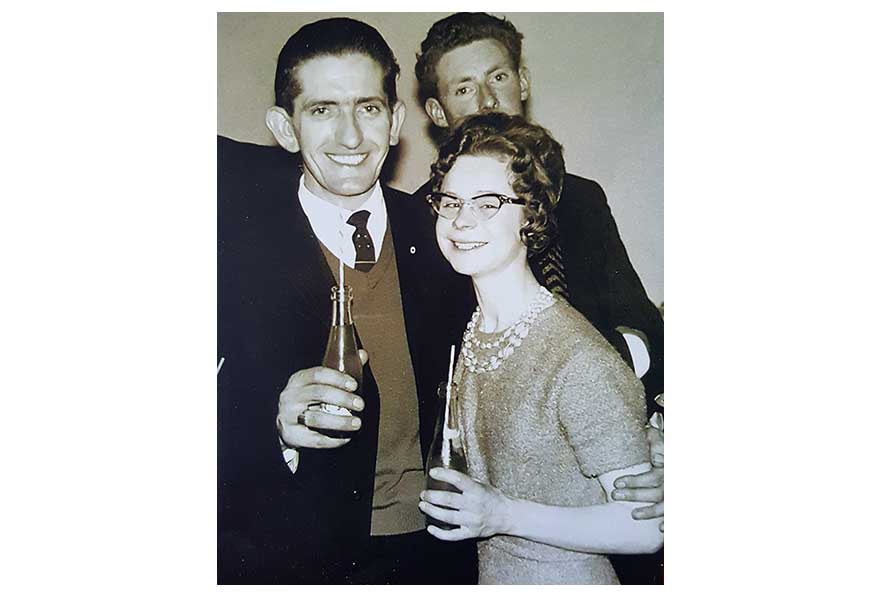

But still, I couldn’t help but wonder. On many of those raucous nights I’d often find myself imagining what places like St Theresa’s were like in their heyday. As I watched the old black and white photos come to life, it certainly seemed a lot busier. Young men in sharp suits were dancing with young women in fine dresses to the tunes of a visiting showband. Over there I can see my parents and their friends sitting at a table, and they’re all looking a damn sight younger than me…

Of course, that was just me romanticising the past. I used to do a lot of that, back when I was sentimental.

For the most part, the Irish of my parents’ generation didn’t come to Birmingham because of its network of canals or extensive collections of pre-Raphaelite art. They came to Birmingham because they were looking for work. When they first arrived they often lived in cramped bedsits or “digs” in inner city areas like Handsworth, Sparkhill and Sparkbrook, and most were prepared to work hard – and work long hours – doing the jobs many of the ‘locals’ didn’t want to do. They were, to use the modern parlance, economic migrants.

“Occupations such as working on buses and trams were rejected by English workers for the higher wages and appealing shorter working hours enjoyed by their counterparts in factories. One contemporary estimated that in just fourteen months in 1946-7 two-thirds of the 6,000 drivers and conductors in Birmingham had resigned and taken other employment. As was the case in London, the local transport authority recruited directly from independent Ireland, continuing in effect a practice initiated during the war that eventually ceased in 1953. By the early 1950s roughly one-third of the transport authority staff were Irish, many of them women. “Enda Delaney, The Irish in Post-War Britain p 97

For sure, Professor Delaney, my Aunt Bella was one of them. Of course, indigenous populations don’t always take kindly to people from other countries “taking their jobs”, and the Irish influx was often greeted with distrust and even hostility. The fact that the jobs the migrant workers were ‘taking’ were the ones that nobody else wanted to do was neither here nor there.

I’m so glad that sort of thing doesn’t happen any more.

When the Birmingham Irish of my parents’ generation first arrived here they worked hard, lived in often squalid conditions, were separated from their loved ones and were often distrusted and disliked. In this context, then, the Irish church clubs in Birmingham played a fairly significant role. With their regular dances and visiting showbands, places like St Theresa’s – as well as those other Patron Saints of the Birmingham Irish like St Chad, St Francis and St Catherine – offered the Birmingham Irish a means to reconnect with their culture, re-engage with their community and have a bloody good time. More significantly, though, if it wasn’t for places like this then people like me probably wouldn’t be here today.

My parents met at a dance at St Chads…

(In memory of my cousin Gerard, who used to work there back in the day)

Irish Brummie Related Stuff from Amazon

[amazon box=”0717116565,1502764563,023029636X,0199686076,0773522131,1902602757,1856350584,B01DBBAATU”]