Some comics are defined as ‘classics’, while others are regarded as influential, innovative titles years ahead of their time. Then there’s Métal Hurlant.

A SURLY, weather-beaten warrior glides over a bizarre landscape, slouched on the back of a grey pterodactyl… an interstellar anti-hero battles Lovecraftian demons through space and time… an incongruous adventurer in pith helmet and khaki tries to save the three-levelled world that he himself created…

Between 1975 and 1987, the French science fiction anthology magazine Métal Hurlant (‘Screaming Metal’ in English) published the maddest, weirdest and most breathtakingly gorgeous comics the world had ever seen. A list of its contributors reads like a roll call of the industry’s finest talent: Jean (Moebius) Giraud, Philippe Druillet, Jean-Pierre Dionnet, Richard Corben, Chantal Montellier, Enki Bilal, Jacques Tardi, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Hugo Pratt, Jean-Claude Gal, and many, many more either made their name, consolidated their reputation, or wholly reinvented themselves within its pages. More than any other publication, it transformed a lowly, juvenile medium into a vibrant ‘ninth art’ and – to this day – continues to exert a powerful influence on the world of comics and beyond.

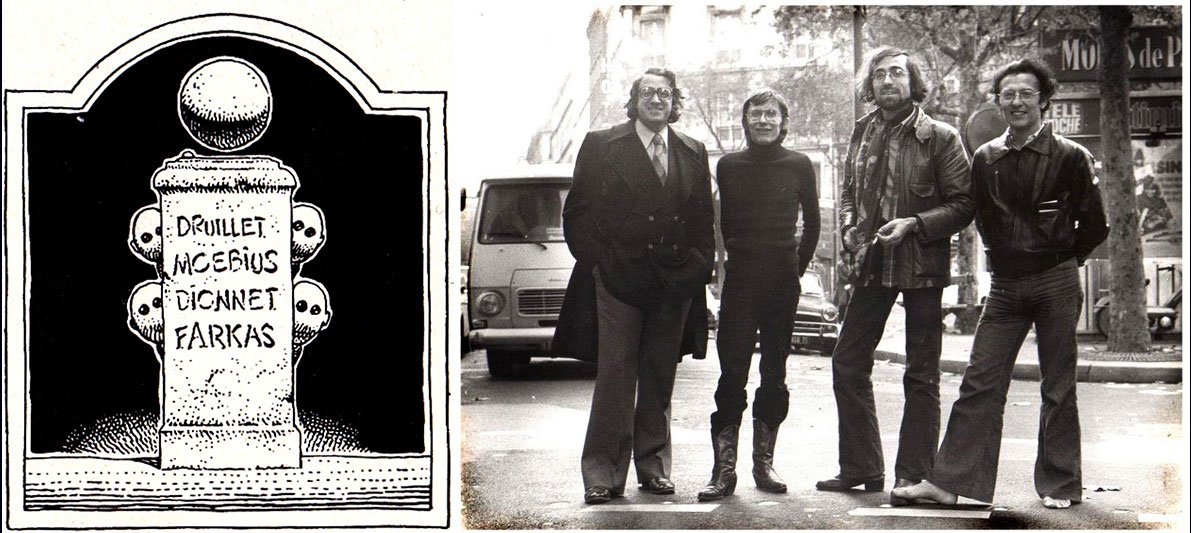

The magazine was launched in January 1975 as the flagship title of Les Humanoïdes Associés, a French publishing venture set up by Euro comic veterans Moebius, Druillet and Jean-Pierre Dionnet, together with their finance director Bernard Farkas. Influenced by both the American underground comix scene of the 1960s and the political and cultural upheavals of that decade, their goal was bold and grandiose: they were going to kick ass, take names, and make the world’s greatest science-fiction comics magazine.

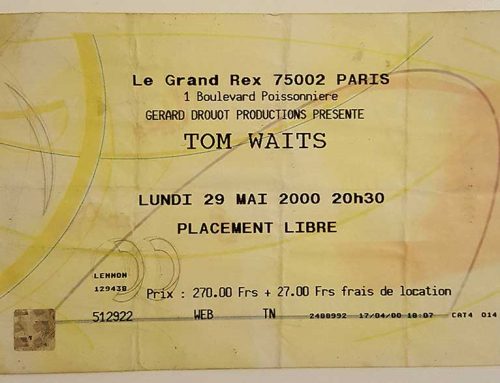

The original Moebius-designed Humanoids logo; The Humanoids founding fathers (l-r), Farkas, Dionnet, Druillet, Moebius

With an emphasis on avant-garde storytelling and Gallic satire, Métal Hurlant was characterized by artistic innovation at every level. In the beige comics world of the 1970s – where cheap, pulpy newsprint was still the industry standard – Métal Hurlant arrived printed on quality stock, allowing its illustrators to create visually stunning, often lavishly painted artwork that seemed to almost explode from the page. Robert Crumb and his underground cohorts might have influenced them, but these Humanoids were clearly not content with making do with underground production values.

It wasn’t just the look of the magazine that was different. The creators, freed from the editorial constraints of traditional comic publishers, were encouraged by editor Dionnet to take risks and push their art into new and unchartered territories. Like the underground titles before them, they didn’t shy away from adult themes, but – more often than not – these elements were shot through with a rich vein of humor and delivered with a narrative sophistication previously unseen in the medium.

This approach was typified by an artist who, more than any other, has become synonymous with Métal Hurlant. Jean Giraud (1938-2012) was a successful comic artist who, under the pen name ‘Gir’, was best known as the co-creator of the popular Western series, Blueberry. By the mid-1970s, Giraud was feeling increasingly constrained by the conventions of the western genre, so decided to revive a dormant pseudonym that would go on to earn him international acclaim. As ‘Moebius’, Giraud not only worked in a different genre to ‘Gir’ – a deeply personal, highly idiosyncratic form of science fiction and fantasy – but his art looked like it was drawn by a completely different person. Where Gir’s brushwork evoked the mythical Old West of John Ford movies, Moebius’s preferred tool was the pen, and with it he created entire universes that were quite unlike anything that had been seen in comics – or, for that matter, in any other medium.

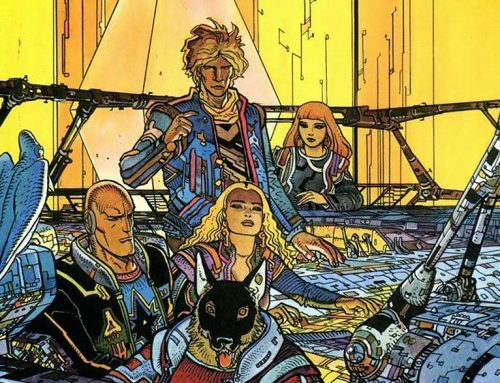

Two of Moebius’s most famous and enduring characters made their debut in early issues of Métal Hurlant. Arzach was a grumpy-looking warrior who explored a strange, desolate landscape on the back of a pterodactyl-like creature in a series of ‘silent’ vignettes. Major Grubert, by contrast, was a pith-helmeted space adventurer – a sort of interstellar Allan Quatermain – whose increasingly unpredictable escapades within the asteroid-encased pocket universes he protected would collectively become known as The Airtight Garage.

Métal Hurlant Gallery: Moebius

As well as these major signature works, Moebius would go on to produce an abundance of classic short stories for the magazine like The Long Tomorrow (his future-noir collaboration with screenwriter Dan O’Bannon) as well as lengthier works like the hugely-influential Incal series (written by cult film director Alejandro Jodorowsky). The very first story to appear in Métal Hurlant – a six-page sci-fi yarn by Moebius and Philippe Druillet entitled Approaching Centauri – typified the spirit of bold experimentation that would come to characterize both the artist and the magazine. As Moebius later recalled:

‘My intention was to see if I could express the same quality of nightmarish visions that always seemed to come so naturally to Philippe. I even used the same extra-large format of paper that he uses for drawing his stories. At the same time, I wanted to retain my own style, and not copy him. In fact, I had the art of French illustrator Gustave Doré in mind when I started drawing the story’.

Moebius wasn’t the only comic artist breaking new ground in Métal Hurlant. His fellow Humanoids co-founders Dionnet and Druillet produced some of their finest work for the magazine. Dionnet wrote Exterminator 17 (a terrific, cyberpunk-anticipating future war series featuring luscious artwork from Enki Bilal) and the heroic fantasy epic Conquering Armies with Jean-Claude Gal”. Druillet, meanwhile, took his already weird-yet-compelling linework to new levels of deranged, baroque brilliance, reviving his classic, dimension-hopping antihero Lone Sloane in the serial “Gail” (1975-76) and his somewhat loose, totally mad, yet utterly mesmerizing adaptation of Gustave Flaubert’s historical novel “Salammbô“ (1980).

Métal Hurlant had become a melting pot of artistic innovation. The magazine played a pivotal role in the development of the influential retro-modernist Atom Style of comic illustration, publishing early work by pioneers of the technique like Yves Chaland, Joost Swarte, Serge Clerc and Ted Benoit. It serialized French translations of classic material from other countries, including “Judge Dredd” from the British anthology comic 2000ad. It also published lengthy articles championing the work of fantasy artists from outside the comics field such as H.R. Giger and Chris Foss.

Métal Hurlant Gallery: Druillet, Bilal & Co.

Like all pioneers, they didn’t always get it right. Some of Métal Hurlant’s bandes dessinées (‘drawn strips’ – the French term for comics) were overly self-indulgent, while others haven’t aged particularly well. Other strips haven’t aged particularly well. To those who adhere to modern, neo-puritan standards, Richard Corben’s groundbreaking fantasy hero Den—a sort of testosterone-charged mashup of pulp hero John Carter and porn star John Holmes—probably reads like the fever dream of a deeply misogynistic nerd. That’s a shame because Corben built fantasy worlds that were astonishing, idiosyncratic, and utterly mad. Den remains his masterpiece, and while it’s most definitely a product of its time, isn’t the fate of everything?

Still, the magazine’s overall artistry and defiant risk-taking agenda inspired rival publishers to up their game, and it wasn’t long before other ‘Bandes Dessinées Pour Adultes’ titles hit the Franco-Belgian spinner racks. In 1977, Les Humanoïdes Associés themselves produced a ‘sister’ publication entitled Ah! Nana, devoted almost exclusively to female comic creators like Chantal Montellier. Similar titles also began to appear in other European countries – like Spain’s Metropol and Italy’s Frigidaire – often featuring translations of Métal Hurlant strips, while in the UK the magazine was a major inspiration behind the classic anthology comics 2000ad and Warrior.

More than a decade before the likes of Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns led to a spate of ‘Bam, Pow: comics aren’t just for kids anymore’ headlines in the English-speaking press, Métal Hurlant was boldly asserting the medium’s maturity. In France, an ‘auteur’ system rapidly developed, with comic creators earning the same kind of cultural esteem as novelists and film directors. Inspired by the legendary highbrow film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, a ‘Cahiers de la Bandes Dessinées’ was launched, subjecting comics to similar levels of intellectual scrutiny (and, some would say, pomposity). University courses dedicated to the subject soon sprang up, and even the French government acknowledged comics newfound legitimacy by bankrolling the huge national comic strip museum in the town of Angoulême. By the time former President François Mitterand confessed he was an avid comic reader in 1985, the French considered it no more controversial or eccentric than admitting a fondness for opera, jazz or the films of Jerry Lewis.

The protagonist awakens to find himself transformed into a muscular giant in a strange, savage world full of dragons, manbeasts and women of ample proportions…

English-speaking comic fans were also becoming increasingly aware of Métal Hurlant. Even those lacking French language fluency were still quite happy to savor the eye-popping artwork, although the nudity probably helped. The publishers of American satire magazine National Lampoon saw a potential for exploiting this new adult comics market and, in 1977, published Heavy Metal magazine, which – during its early years, at least – devoted itself almost exclusively to translated reprints from Métal Hurlant.

Heavy Metal magazine became a Stateside hit, and even spawned an animated film in 1981. Before long, other American comic publishers wanted a piece of this adult comic action. In an interview with the website Comic Book Resources, former Marvel Comics Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter recalled an incident from the 1970s:

‘Before the publication of Heavy Metal, [Les Humanoïdes Associés] came to Marvel seeking an American publisher. After they did their presentation, we had a talk and [Stan Lee] thought that the stuff was too violent, too sexy and that good ol’ sanitized Marvel couldn’t do that.’

Heavy Metal’s success was enough to encourage a change of policy, however. In 1980 Marvel launched Epic Illustrated, which – whilst toning down the sexual and satirical content to broaden its appeal – was published in a similar format to the illustrious French original. Uneven but occasionally brilliant, it featured stunning work from the likes of Frank Frazetta and Hurlant regular Richard Corben. Ironically enough, in the late-1980s Stan Lee collaborated with Moebius on a Silver Surfer comic, and Marvel’s Epic imprint released a series of Moebius graphic novels featuring the same Métal Hurlant material that he’d previously felt was a bit too much for his ‘True Believers’.

Métal Hurlant’s impact on comics:

Sadly, the irony didn’t stop there. Back in France things weren’t going well for Métal Hurlant. The magazine was no stranger to financial difficulties, hardly surprising given the fact it was originally set up by three visionary iconoclasts and a token businessman. In 1980 the Spanish company Litoprint stepped in to become its main shareholder, while Dionnet, exhausted by years of creative and financial battles, left the magazine. In 1986, Litoprint sold the publishing company and the magazine to the media giant Hachette, but by then the French comics industry had changed dramatically. Readers were increasingly inclined to wait for graphic novel-style collections of previously serialized strips, a publishing phenomenon Métal Hurlant’s founding fathers had pioneered. Traditional anthology comic magazines saw their circulations decline, and Métal Hurlant was no exception. In August 1987 – just as headlines about comics growing up started appearing in the British and American press – Métal Hurlant folded.

The magazine was briefly revived in 2002 as Franco-US co-production, and more recently some of its stories were adapted into a TV anthology series entitled Métal Hurlant Chronicles. During its original twelve-year run, Métal Hurlant did more than any other publication to promote comics as a legitimate art form. It not only left us with a formidable back catalog of timeless material, but it became a template for all subsequent attempts at ‘serious’ comics, encouraging writers and artists to aim higher and strive for artistic originality.

That’s impressive enough, but Métal Hurlant’s influence doesn’t end there…

A private eye and his beautiful client make love. The phone rings. It’s a robocop, and it knows who the Arcturian spy is: “It’s the girl!” Suddenly, she changes…

When Métal Hurlant first appeared in 1975, it must have seemed like a crazy idea. Here was an expensively-produced science fiction magazine coming out at a time when science fiction was anything but fashionable. Nowhere was this more evident than at the local cinema, and while the early-70s produced an occasional genre movie classic like Silent Running (1972), most sci-fi films of the period were dour, dystopian, low-budget affairs. This was the era of the New Hollywood directors like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, filmmakers more interested in gritty realism than spaceships and bug-eyed monsters. Métal Hurlant had arrived at a time when mainstream cinema was more interested in the gutter than the stars.

All that changed in 1977. Star Wars was a global sensation that made sci-fi a permanent fixture at the box office. To audiences of the time, this epic space fantasy with its state-of-the-art visual effects looked like nothing they’d ever seen before.

To readers of Métal Hurlant, however, it all looked a bit familiar.

The cluttered, lived-in backdrop of this galaxy far, far away might have looked like it was a dozen parsecs away from the clean, white plastic-panelled corridors of previous sci-fi movies, but this grungy aesthetic was commonplace in the pages of Métal Hurlant. Darth Vader and the Empire, with its penchant for enormous, visually impressive yet somewhat impractical weaponry, evoked the works of Philippe Druillet, while farmboy hero Luke Skywalker’s inhospitable desert homeworld, Tatooine – with its junkshop tech and strange skeletal creatures half-buried in the sand – looked like an Airtight Garage strip by Moebius brought to life.

Métal Hurlant and Star Wars

Director George Lucas made no secret of the connections between Star Wars and Métal Hurlant. He name-checked both Druillet and Moebius in a 1979 interview, wrote introductions to collections of their comic art, and even hired Moebius as a conceptual artist for his late-80s fantasy film, Willow. In fact, a background detail from Moebius’s The Long Tomorrow would later appear as the Imperial Probe Droid in the Star Wars sequel, The Empire Strikes Back.

To be fair, Métal Hurlant was just one of a multitude of sources that influenced George Lucas, and it wasn’t even the only Franco-Belgian comic: the Valérian saga by Pierre Christin and Jean-Claude Mézières (1967-2010) contains many sequences that bear an uncanny similarity to iconic scenes that would later appear in Star Wars films. By opening the door to big-budget science fiction blockbusters, however, Star Wars paved the way for other filmmakers to channel the Métal Hurlant influence even more directly. The Mad Max films of Australian director George Miller – including last year’s Fury Road – all owe a huge debt to Métal Hurlant strips like Druillet’s Salammbô and Jeremiah by Hermann Huppen. The original Mad Max logo even appears to be a homage to the magazine, right down to its dual lightning bolt backdrop.

Ridley Scott – director of two of the most influential science fiction films of all time, Alien and Blade Runner – was quite open about the debt he owed the magazine. In an interview published to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of Alien, he said:

‘In 1977, I came across the comics and publications born out of the Métal Hurlant magazines. In the same year, I was offered Alien, and I recognised the […] influences I could apply to the visual aspects of the film.’

Scott hired Moebius and fellow artists H.R. Giger and Chris Foss (who had both been profiled in Métal Hurlant) to work as conceptual artists on the film, and the Giger-designed alien ‘xenomorph’ remains one of cinema’s most disturbing creations. For Blade Runner, the director turned to Moebius’s aforementioned The Long Tomorrow story and the works of Hurlant regular Enki Bilal to inform his seminal vision of a future Los Angeles. More recently, Scott revisited The Long Tomorrow and other Moebius stories as visual inspiration for his Alien prequels, Prometheus and Alien: Covenant.

Slideshow: Métal Hurlant impact on Movies

And it wasn’t just Hollywood. In Japan, the artist and filmmaker Katsuhiro Otomo cited Métal Hurlant as an influence on his classic manga and anime film, Akira, while Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki took inspiration from Moebius’s Arzach when creating his classic Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Moebius and Miyazaki became close friends and mutual influences: Moebius named his daughter Nausicaä, and in 2005 the artists’ work appeared together in a joint exhibition in Paris.

A decade after it originally ceased publication, the magazine’s legacy returned home. Luc Besson’s 1997 French sci-fi film The Fifth Element may have divided critics, but no one could deny it was bold, visually unique, and one of cinema’s weirdest summer blockbusters. It was also Besson’s love letter to the Métal Hurlant school of comics. Based on a story he started writing at the age of sixteen (in 1975, the year the magazine was launched), it featured production designs by Hurlant alumni Moebius and Jean-Claude Mézières, and remains one of the most expensive works of fan fiction ever made. More recently, Besson returned to the world of French sci-fi comics with Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, his big-budget adaptation of the classic Star Wars-influencing series by Mézières and Pierre Christin.

Filmmakers weren’t the only people indebted to Métal Hurlant. In a 1992 interview, author William Gibson – known as ‘the Godfather of Cyberpunk‘ – remembered a lunch date with Ridley Scott where they discussed their common influences and ‘were both very clear about our debt to the Métal Hurlant school of the 70s.’

In an introduction to the comics adaptation of his novel Neuromancer, Gibson elaborated on this:

‘So it’s entirely fair to say that the way Neuromancer-the novel “looks” was influenced by some of the artwork I saw in Heavy Metal. I assume this must also be true of John Carpenter’s Escape from New York […] and all other artefacts of the style sometimes dubbed “cyberpunk”. Those French guys, they got their end in early!’

These movies and books have effectively channeled the vision and artistry of Métal Hurlant to a global audience, many of whom probably wouldn’t dream of reading a science fiction comic, let alone a saucy French one from the 70s. Star Wars, Mad Max, Alien, Blade Runner – the animated odysseys of Studio Ghibli and the cyberpunk novels of William Gibson – have all inspired countless imitators of their own. These fictional landscapes have been absorbed into our collective imaginations, manifesting themselves in the unlikeliest of places – from music to video games, from the hi-tech exoskeletal excess of the Lloyds Building in London the off-the-shelf Futurist garments so ubiquitous on fashion catwalks – and, ultimately, all of this can be traced back to Métal Hurlant.

Like it or not, we are all Humanoids now.

A significantly updated and expanded version of this article appears in the first volume of the new Metal Hurlant (2025) published by Humanoids. As an Amazon Affiliate I can earn a commission if you click this link and make a purchase at no additional cost to you.

- Bendis, Brian Michael

- Fraction, Matt

- Claveloux, Nicole