T

here’s nothing like a romantic triangle to bring the best out in a fictional character. When a hero is forced to choose between two competing suitors – or a protagonist competes for a lover’s affection – story thrives as dilemma gives way to choice and change. Moreover, the audience witnesses a time-honoured dramatic convention unfold, one that can be traced back to Ancient Greece and those heady days when Ares and Aphrodite snuck off to do the dirty on Hephaistos. Comics, of course, are no stranger to this saucy geometry. From Popeye, Olive and Bluto through to Cyclops, Jean and Wolverine – by way of Lois, Clark and Lana – creators have continued to utilise the romantic triangle as a source of dramatic conflict. One title, though, explored this theme like no other, and – even though its last instalment was originally published over seventy years ago – it continues to enchant new generations of readers with its breathtaking innovation, sublime beauty and peerless artistry.

Published between 1913 and 1944, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat featured one of the most delightfully bizarre variations of the romantic triangle ever to appear in fiction. In the first corner sat Krazy – a simple-minded, “heppy go lucky” cat of indeterminate gender – who passionately loved Ignatz Mouse. Ignatz, though, hated Krazy – a sentiment he invariably conveyed through the medium of a brick thrown at the ‘fool kat’s’ head. Occupying the third corner was gruff, ‘kanine constable’ Offissa Bull Pupp, who secretly held a candle for the kat and tried to protect him/her (remember, indeterminate gender) from Ignatz’ violence by throwing the ‘l’il sinnah’ into jail at every opportunity. That set-up alone might have made for a memorable comic strip. What made Krazy Kat special, though, was a simple conceit added to the mix: Krazy misinterpreted each of the bricks thrown by Ignatz as declarations of love – ‘missils of affection’ from his ‘l’il angil’ – and smiled wistfully each time one clobbered his skull…

This ‘komedy of errors’ was set against the psychedelic, perpetually morphing sands of Coconino County, a madcap landscape that was based on Herriman’s beloved Monument Valley in Arizona. Coconino was a place where the laws of physics and causality were ignored, where a house could change into a cactus plant between panels and characters would traverse the world in the space of a sentence. The language of the strip, too, was equally wild and chaotic. Characters spoke in ethnically diverse, phonetic dialects that were shot through with the rhythmic beat of the Jazz Age. Krazy’s speech patterns, for instance, were an idiosyncratic blend of patois, pun and portmanteau that now read like a bizarre splicing of James Joyce and Jar Jar Binks.

But don’t let that put you off.

While the words and images of Krazy Kat were spontaneous and surreal, these madcap improvisations were strictly aligned to Herriman’s coordinates of compulsion. The apotheosis of this, of course, was its infamous romantic triangle.

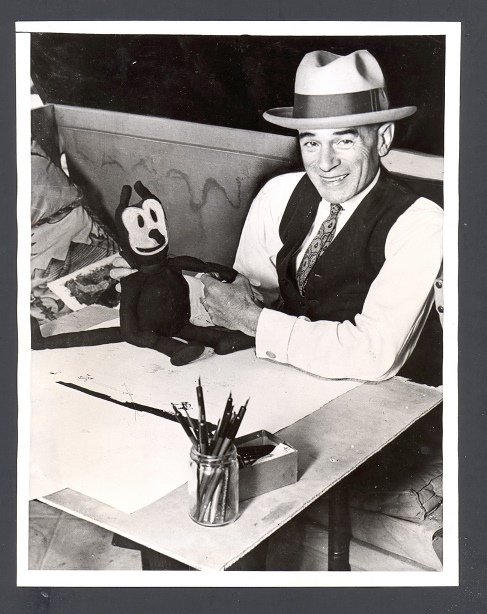

Photo of Krazy Kat creator George Herriman, from the San Francisco Examiner archives (via stwallskull.com/King Features Syndicate, Inc)

In comics, as in any other storytelling medium, romantic triangles are usually resolved when a character makes a choice, gets chosen or winds up being rejected. Even superhero comic strips – notorious for their avoidance of meaningful closure – obey this principle. When the Fantastic Four’s Invisible Woman finds herself torn between the dependable –but-dull Reed Richards and the fanciable-but-fishy Sub-Mariner, we know she’ll ultimately have to choose between the two. Granted, the outcome might be so predictable that a glass eye up a duck’s arse could see it coming – and the dilemma might reoccur time and time again – but at least we know she has a choice.

With Krazy Kat, though, things were significantly different. For one thing, the situation couldn’t be resolved. Closure wasn’t built into the design. The triangle was constructed like an emotional Hofstadter strange loop, and the characters were forced, quite literally, to repeat themselves. In this sense, the romantic triangle transcended the status of narrative device. It became the fundamental essence of the strip, its raison d’etre. Just as jazz musicians structure their improvisations around repeated chord progressions, Herriman anchored his own wild dance of word and image to the central dynamic of the triangle, creating thousands of strips that explored the endless permutations of this bizarre yet deeply ironic set-up.

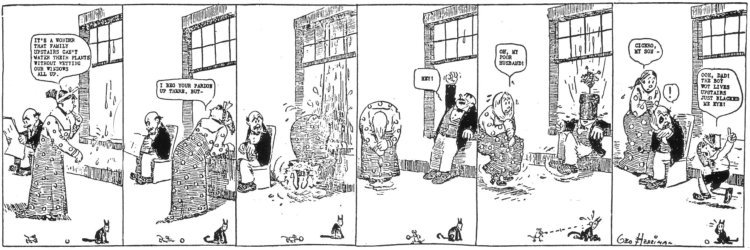

The elaborate cat-mouse-dog triangle was not fully formed at the strip’s inception, however, but was something that developed organically over time. As Herriman himself once admitted, “Krazy Kat was not conceived, not born, it ‘jes grew,” and the character’s first appearance was inauspicious to say the least. In 1910 he was illustrating The Dingbat Family, a daily sit-com strip for the New York Evening Journal. Along the bottom of the instalment dated 26th July 1910 – and done, according to Herriman, just ‘to fill up the waste space’ – a mouse sneaked up on the family cat and threw a projectile at its head. This throwaway gag turned out to be the catalyst – or, ahem, katalyst – for all that followed.

The Dingbat Family (26th July 1910), featuring Krazy Kat’s first ‘beaning’ by Ignatz Mouse (King Features Syndicate, Inc)

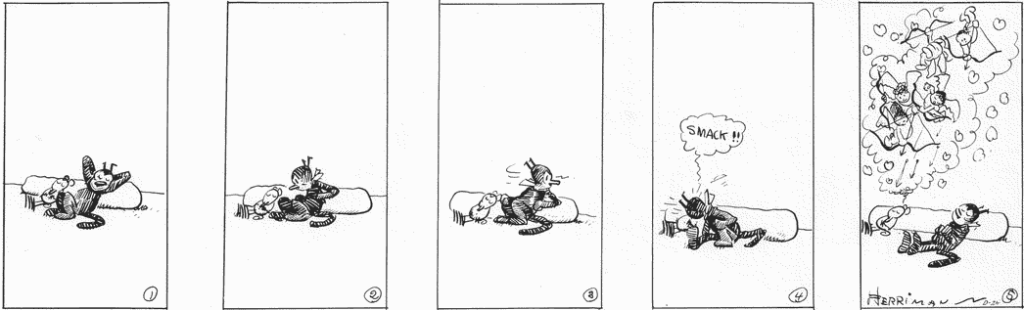

After a month or so of these daily beatings, Herriman introduced us to the next ironic layer: as Ignatz slept, Krazy crept up to the mouse and planted a big sloppy kiss on his brow. The straightforward slapstick and comic role-reversal of the first movement had now evolved into something more complex and sublime. Ignatz’ brick – a symbol of his obsessive hatred for Krazy – would now be interpreted by the kat as a signifier of love. For Krazy, each ‘beaning’ would become a declaration of desire, a meaningful bouquet of brick.

Krazy and Ignatz’ adventures continued appear as a supporting feature underneath the main Dingbat Family title until 1913, when they finally earned a daily strip of their own. When Krazy Kat subsequently gained a weekly Sunday page in 1916, Herriman’s artistry took a giant leap forward. Freed from the five-panel straitjacket of ‘the dailies’, he now had the leverage to create more innovative layouts. In terms of panel composition alone these pages were design classics. Herriman was experimenting with the way the shape, size and texture of a panel could effect the mood and overall ‘timing’ of the strip before Frank Miller was born and while Will Eisner was still in diapers. Herriman’s linework had also evolved, as he effortlessly switched between the use of a few scratchy, perfectly delivered lines to capture the image and essence of Krazy and Ignatz, and the delicate, cross-hatched chiaroscuro of the Coconino backdrop.

Herriman used the early Sunday pages to tell more elaborate Krazy-Ignatz gags. In a strip dated 17th June 1917, for instance, Krazy discovered an Ouija Board and asked it: ‘Weeja, Weeja, who is it I got for a “enemies”?’ When the planchette spelt out I-G-N-A-T-Z, Krazy smashed the board and cried out: ‘T’aint so!! T’aint so!! Ignatz is my friend!’ When Ignatz subsequently discovered the broken board he threw a brick at Krazy’s head as punishment. To Krazy, of course, this act was proof that the Ouija Board lied.

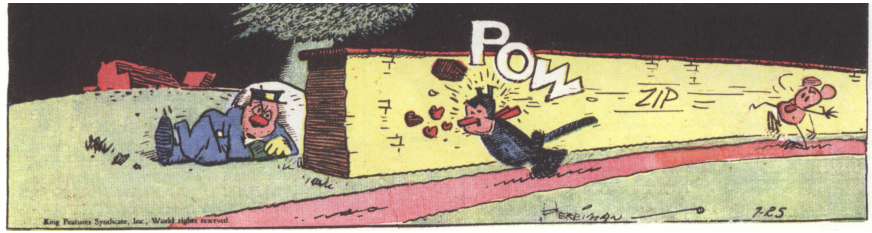

Gallery: Krazy Kat B&W Sunday pages, 1916-1934

Herriman also used the Sundays to expand on his cast of supporting characters. During this period, Coconino County’s array of anthropomorphic regulars incorporated Kolin Kelly (‘Dealer in Bricks’); Bum Bill Bee (‘Pilgrim on the Road to Nowhere’); Joe Stork (‘Purveyor of Progeny to Prince and Proletariat’) and Joe Bark (‘The Moon Hater’). Herriman also resurrected characters from earlier, less successful strips like Don Kiyote (‘Psalmsinger of the Desierto Pintado’) and Gooseberry Sprigg (‘The Duck Duke’). Together, these characters provided both an amusing commentary and apt counterpoint to the Krazy-Ignatz relationship. One supporting character from this era, though, was destined for much bigger things.

Offissa Pupp had been a minor player since the strip’s earliest days, but a private declaration of love for Krazy pushed him to the foreground: ‘Oh, would that I were a klown instead of a kop oh, would that my forte be komedy instead of konstabulary – that I might bring a smile to that wan, wasted, wistful pan of that dear Kat.’ With those words, another rich layer of irony was added as Krazy and Ignatz’s demented dialectic evolved into a misunderstanding-fuelled ménage à trois. To the oft-repeated strum of Ignatz ‘beaning’ Krazy with a brick a new note was added: the discordant clang of Pupp throwing Ignatz into jail.

The emphasis on this strange relationship was underscored by the ‘stripped down’ approach to Krazy Kat’s art that Herriman was now adopting. Prompted by the imposition a new standardised grid layout – a change that Herriman resisted – his linework had become more scratchy and raw. The Coconino backdrop was gradually relieved of its shops, country houses and other tokens of minor urbanity and the action increasingly took place out on the sands of this morphing, dream-like landscape. The characters, too, underwent a change. As the emotional stakes were raised, so too was the intensity of their compulsions. Ignatz, for instance, became even more obsessive in his schemes, with each throw of the brick becoming more elaborate than the last.

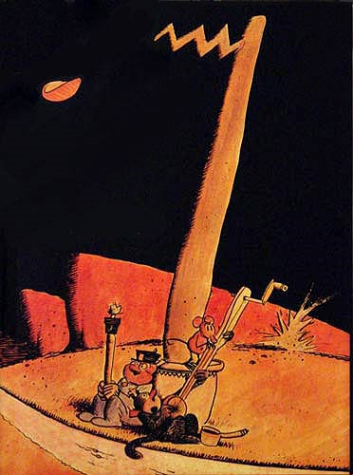

Gallery: Krazy Kat colour Sunday pages, 1935-1944

The next stage in the evolution of the Krazy-Ignatz-Pupp triangle coincided with another change on the production value front, namely, the introduction of colour to the Sunday strip in 1935. Unlike the imposition of the standardised grid, this was a change that Herriman embraced wholeheartedly. He used a full, bold palette to transform Coconino into a phosphorescent, psychedelic landscape encased in large, geometric panels. A purple cactus plant w ould grow from the green sands beneath the shadow of a ruby red mesa. In the next panel, of course, the objects – and now their colours – would all change again. His linework, too, had come a long way from the delicate cross-hatching of the early Krazy Kat strips, as Herriman used a bold, deeper line to contain the colour. Krazy, Ignatz and Pupp also underwent a visual change. They became chunkier, more stylised and further removed from their animal origins (in one daily strip a supporting character had to remind them of their ‘atavism’). Significantly, the cast was whittled down to just Krazy, Ignatz and Pupp, with only a few ‘extras’ now allowed out to play. The language of the strip also evolved. The lengthy, poetic ramblings that had once characterised the dialogue now gave way to a tight, haiku-like minimalism. The strip was still rich in humour, of course, but the slapstick and burlesque of the early years had now given way to a subtle, slow-burn comedy: a knowing phrase or sideways glance was now enough to deliver a more subtle kind of meaning. These were jokes without punchlines and prefigured the kind of surreal comedy of repetition that popular taste is now more accustomed to.

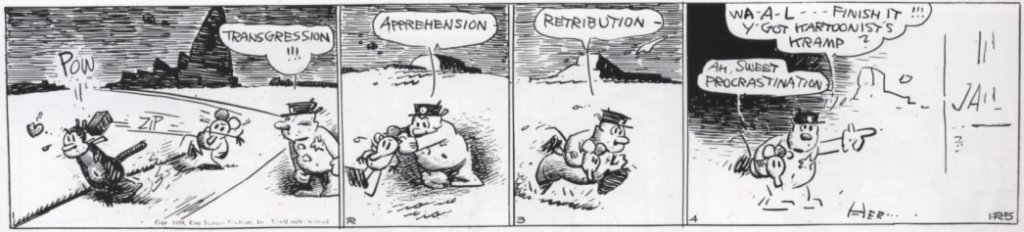

At the heart of the strip’s increasingly esoteric humour, however , remained the romantic triangle. This had transcended the status of mere narrative device. It was no longer just an aspect of the strip: Krazy Kat was its romantic triangle. The gags only worked if the audience understood the inherent matrix of misunderstanding. The strip only made sense to those who could grasp that a brick to the head can mean different things to different people. In a daily strip from 1939, for instance, Offissa Pupp witnessed Ignatz beaning Krazy with a brick and said: “Transgression!!!” In panel two, Pupp reached out to grab Ignatz: “Apprehension!” In panel three, Pupp hauls Ignatz off to jail: “Retribution!” On the final panel, they reach an incomplete drawing of the jail. “Finish it!!!” demands Pupp, looking straight out of the panel at an imaginary Herriman, “Y’ got kartoonists kramp?” Not for the first time in Krazy Kat’s history, post-modernism pre-dated the term.

The stripped-down, cerebral subtlety of latter-era Krazy Kat hardly endeared it to new or even casual readers, however. By the time Herriman died in 1944 it was only appearing in thirty-five newspapers, a miniscule number compared to other syndicated strips of the era. What Krazy Kat lacked in popular success, however, it made up for in critical acclaim. Amongst its admirers were some of the artistic figureheads of the last century, including Picasso, James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Jack Kerouac. The strip’s longevity – and survival during lean periods – was due to the unlikely patronage of that most monolithic of press barons, William Randolph Hearst. After Herriman’s death, Hearst took the unprecedented step of cancelling the strip. Krazy Kat had become so synonymous with Herriman that a replacement was out of the question.

In the decades that followed, its reputation has continued to grow. In 1999, the esteemed The Comics Journal declared that Krazy Kat was the most significant comic strip of all time. Contemporary fans include Quentin Tarantino (whose Pulp Fiction featured Samuel L. Jackson in a Krazy Kat t-shirt) and REM’s Michael Stipe (who sports a Krazy and Ignatz tattoo on his arm), while The Simpsons’ “Itchy and Scratchy” running gag is carto onist Matt Groening’s thinly veiled homage to the strip. Its lasting appeal is due to the fact that – unlike many other vintage comic strips – it doesn’t seem dated. There’s a rhythm to Krazy Kat that remains timeless and universal. Sure, you might not notice it at first, but listen close and you’ll hear it. Out beyond those morphing backdrops and that crazy, improvised language there’s a noise that’s familiar to us all. If you’ve ever found yourself caught up in a romantic triangle or endured the linear misery of unrequited love, it’s a sound you’re bound to recognise: it’s that unmistakable THWACK of a brick to the back of the head.

The illustrations featured in this article were culled from these sources, and I can’t recommend them highly enough.

This article first appeared in Borderline Comics Magazine.

Further reading

For more Coconino County-based brick-on-cat action, you might want to check out Fantagraphic Books’ wonderful 13-volume collection of Krazy Kat Sunday strips (each featuring a breathtakingly sublime cover by award-winning comic artist Chris Ware). A selection of those can be found below, as well as Michael Tisserand’s 2016 Herriman biography, “Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White”. As an Amazon Affiliate, I can earn a commission if you click these links and make a purchase at no additional cost to you.

[…] As we muse on the micro, we might lament that fact that it was on this date in 1944 that the final installment of George Herriman’s comic strip Krazy Kat appeared– exactly two months after Herriman’s death. The strip– aguably the best ever; inarguably foundational to the form– debuted in New York Journal (as the “downstairs” strip in Herriman’s predecessor comic, The Dingbat Family (later, The Family Upstairs). Krazy, Ignatz, and Offisa Pup stepped out on their own in 1913, and ran until 1944– but never actually succeeded financially. It was only the admiration (and support) of publisher William Randolph Hearst that kept those bricks aloft. […]

[…] vertiginous dreamscapes of Winsor McCay (creator of Little Nemo) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat). Gelman would also be a source for the freelance work designing satirical bubble-gum cards (most […]

[…] vertiginous dreamscapes of Winsor McCay (creator of Little Nemo) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat). Gelman would also be a source for the freelance work designing satirical bubble-gum cards (most […]

[…] vertiginous dreamscapes of Winsor McCay (creator of Little Nemo) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat). Gelman would also be a source for the freelance work designing satirical bubble-gum cards (most […]

[…] vertiginous dreamscapes of Winsor McCay (creator of Little Nemo) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat). Gelman would also be a source for the freelance work designing satirical bubble-gum cards (most […]